Ingenious Imitations

Cornelius Krieghoff’s acclaimed paintings of nineteenth-century Canada are found in galleries and private collections around the world. But many of the works attributed to him are actually forgeries.

By Jon S. Dellandrea

Written for Canada’s History, June 1 2021

See Original Published Artice Here

Shoppers browse for deals in The Lanes in Brighton, England. (Alamy FTJ7G4.)

I AM AN ART COLLECTOR. This story is about how hundreds of “Cornelius Krieghoff” paintings held by galleries and private collectors in Canada and abroad are in fact brilliantly reproduced fakes. This story is not a work of fiction, and none of the names have been changed to protect the guilty. This is the true account of a quite remarkable period of a modern Wild West art world in which gunslingers (well, brush slingers) ran free on the creative range.

Let’s set the scene: It was the 1960s, and in “The Lanes” of Brighton, England, anything could be bought. You could take your pick from “genuine” historical sculptures to great paintings by some of the world’s most famous artists. And you could buy them at a fraction of the prices realized at auctions or tony London galleries. The Lanes were warrens of stalls and shops with dealers set up along the sidewalks. This was Portobello of London, the flea markets of Paris, and the Stanley Market of Hong Kong all rolled into one. Treasures could be found in every stall and around every corner. And, when the treasure hunting was complete, one could find several excellent restaurants nearby. One such establishment was run by an affable Italian who decorated the walls of his establishment with art, all of which was for sale.

Some of the pictures on the walls of La Dolce Vito were genuine. Bonaveri and his restaurant acquired a bit of fame when Canadian industrialist Alfred Bader and his wife, Isobel, patrons of the restaurant, purchased a small dirty painting off Bonaveri’s wall.

Bader described the discovery this way: “Years ago, Isobel and I were wandering around Brighton in Sussex, England, looking for somewhere to have a minestrone for lunch. We went into a small restaurant owned by an Italian Gabrio Bonaveri. On the wall were many paintings for sale.” Bader then recounted in a story in the Queen’s Alumni Review how for 600 pounds sterling he purchased the painting Adoration of the Shepherds and how Bonaveri was so pleased with the sale that he did not charge the Baders for their minestrone.

Bader obviously had an eye as good as Bonaveri’s, as the dirty little painting was authenticated by the venerable auction house Christie’s as the work of none other than the Greek artist El Greco (1541–1614). The masterpiece then went through a sale at the auction, with the purchase price covered by Bader and the painting subsequently donated to Queen’s University (Bader’s alma mater) in Kingston, Ontario. In the Queen’s Alumni Review story, Bader described the transaction:

“I sent the painting to Christie’s, who accepted it as attributed to El Greco, although it was unpublished. I promised Queen’s to cover whatever price it reached at auction and, many years after we bought it, it arrived safely at Queen’s.”

La Dolce Vito closed in 1993, and paintings that had graced the walls at the time of the closing, as well as those in Bonaveri’s storage room, began to appear on the market. Among this collection were a number of excellent examples of the “potboiler” works of Cornelius David Krieghoff.

Marie of Montreal, also known as A moccasin seller outside the artist’s studio, is a circa-1849 painting possibly by Cornelius Krieghoff or Martin Somerville. The artists had studios in the same building in Montreal between 1845–55 and shared a similar style. (Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea.)

A word or two on the nature of the potboiler business: Cornelius David Krieghoff (1815–72) was a seriously talented artist. Scholars such as Dennis Reid, Raymond Vezina, and J. Russell Harper have studied his work and written about his life. Notwithstanding the Dutch Canadian’s artistic talent, he also needed to make a living, and good money was to be made by mass producing souvenir paintings to be flogged to British garrison soldiers in Montreal and Quebec in the 1840s. These small, often twenty-by-twenty-five-centimetre paintings were potboilers, so named for providing the artist with the means to “boil the pot” — that is, pay for essentials like food.

Krieghoff and another artist, Martin Somerville, had studios in the same stone building at 26 St. James Street in Montreal, and they produced similar works. Surviving from this period is a lovely painting, entitled Marie of Montreal, of a Caughnawaga woman standing in front of the building circa 1849. She is holding moccasins for sale. The painting is pictured in J. Russell Harper’s 1979 book Krieghoff.

Marie of Montreal reappeared in London, England, on April 1, 2015, at the Christie’s sale of items from the Winkworth Collection that had been amassed by Peter Winkworth (1929–2005). Christie’s held a sale preview at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto. There, art historian Dennis Reid and I had the pleasure of standing side by side viewing what Reid described as “alovely little picture.” The painting was offered as attributed to either Cornelius Krieghoff or Martin Somerville. Even though the moccasins are wrong, I believe it to be Somerville’s work — but who knows?

I will now make a personal confession: I was the underbidder at the Christie’s auction for this painting, and it is the only painting that I have ever deeply regretted not buying. I set an upper limit on what I was willing to bid and missed the purchase by a few thousand dollars. My consolation prize was another smaller version of Marie of Montreal attributed to Somerville that now hangs proudly on my wall. over time the art passed from one generation to the next. The value of the paintings increased substantially with each passing generation. One can imagine the excitement of a patron of La Dolce Vito spotting a small Krieghoff for sale at a modest price on the walls of the restaurant.

I am an art collector, an art detective, a writer, and an art historian, but most of all I am a treasure hunter. I love finding lost interesting things that turn up mysteriously. While I was in university, my future mother-in-law and I dug through an abandoned nineteenth-century railway dump, discovering antique bottles and pots. (I financed a bit of my university education by selling them.) As scuba divers, my wife, Lyne, and I explored the depths of the Mattawa and St. Lawrence rivers. As antique and Canadiana collectors we haunted the weekend markets and country auctions in search of treasure. But then, in the mid-1990s, along came eBay. This was a treasure seeker’s dream. Millions of items from all over the world were suddenly at our fingertips. A revolution was happening in the art world. Overnight, the volume of available art increased exponentially. Somewas good, some great, some terrible, some genuine. And then there were a whole lot of fakes.

But back to the story of how I got involved in all of this. In 2014, twenty-one years after the closing of Bonaveri’s restaurant, a rather attractive Krieghoff potboiler depicting an Indigenous hunter on snowshoes was offered for sale on eBay. I corresponded with the sellers, Peter and Joanna Bryan, and learned that the painting had come from an Italian restaurant that had operated near Brighton, England. A purchase of this painting, at a not totally modest price, was negotiated, and thus began this journey of discovery.

Joanna Bryan wrote to me and said, “There are, I think, other examples of these works in the garage. I will do my best to empty out the garage and find them. I know that another buyer bought some of Gabrio’s collection that decorated the restaurant. I will ask him if he has anything left from the parcel, although I remember that initially he put some through the local auction. It is worth asking him, however.” One month later Joanna Bryan wrote back to say, “The garage and shed yielded three additional snow scenes which were stored on edge in a box. They had become a little dirty as I suspect that the surface of the paint was a trifle sticky from their days in the restaurant, with the nicotine and catering activities. They are being lightly cleaned and revarnished.”

Far left: A genuine Cornelius Krieghoff painting, Indian Woman, Moccasin Seller, was created circa 1855. (Photo © Christie’s images / Bridgeman images.) Centre left: A Krieghoff forgery, The Moccasin Seller. (Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea / Photography by Doug Nicholson.) Centre right: Krieghoff’s Indian Hunter, painted circa 1855. (The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario, 2009/401.) Far right: Indian Hunter on Snowshoes, a forged Krieghoff. (Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea / Photography by Doug Nicholson.)

Over the subsequent two years I acquired another ten paintings from the Bryans that had clearly been executed by the same hand. The burning question was, whose hand? Krieghoff? Somerville? Or someone else entirely? The signatures were right. The canvasses and stretchers were mid-nineteenth century. The subjects were accurate, but something was just not right. The Krieghoff paintings that I acquired from Joanna and Peter Bryan over several years were “cleaned” before they were sent to me. Upon receipt of said paintings I was gobsmacked!

They were bloody brilliant. And therein lay the problem. They were too brilliant.

The small canvasses were old and grubby on the back and clean and shiny on the front. The images were delicately done. The skies were perfect Krieghoff skies. The snow puffed up through the hunter’s snowshoes, and the snowflakes were divine. The paintings were so clean that it was hard to imagine that they had been painted 175 years ago. Was it more likely that they had been painted forty years or so ago, about the time Bonaveri opened his restaurant? And, if so, by whom?

Top: Two Krieghoff forgeries, likely painted by art forger Max Brandrett, were purchased by the author in Brighton, England. Below: The author’s fake Krieghoffs were painted on old canvasses and mounted on authentic-looking canvas stretchers, helping to create the illusion that the paintings were indeed genuine. (Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea / Photography by Doug Nicholson.)

Why did I keep acquiring these suspect paintings? I guess I did it because they were enigmatic mysteries. The paintings found their place on my walls, and I enjoyed looking at them every day. But this little project of discovering their true provenance was tucked away as I diligently tried to finish writing the book on the subject of the famous Canadian art fraud case of 1962–64. This concerned a flood of Canadian art forgeries of the works of well-known painters, including members of the Group of Seven. The Brighton Krieghoffs project would most likely have remained on the shelf were it not for an email I received in early October 2020 from Peter Bryan. The email was to apologize for not having adequately responded to my request some years earlier for more information about the origins of the paintings.

Now for a bit of background on the Bryans: Peter was born and raised in Brighton. As a youngster he hung out in Brighton’s pool halls with the “knockers,” some of whom went on to become big international dealers. (A knocker is someone who goes door to door looking for old art and antiques to buy at bargain prices and, in this case, intends to resell them in The Lanes of Brighton at a considerable profit.) Over his career Bryan was a model, an art dealer, an artist, a Brighton pub owner, and a friend of Gabrio Bonaveri. Peter Bryan met Joanna in the 1970s when she was a student at Eastbourne College of Art. Together they sold more than a few paintings over the years. Joanna was also a friend of Bonaveri, and Peter had met Max Brandrett, a local forger, years earlier through a fellow tavern keeper. Brighton was a small world, and art, both genuine and fake, was at its centre.

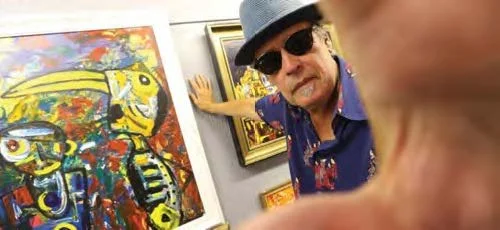

Over the days following Peter Bryan’s initial email, he and I had a series of fascinating exchanges about the characters and forgers of twentieth-century Britain. I learned about Tom Keating, one of Britain’s most famous forgers; of David Henty, now regarded as the best forger in the world; of William Mumford, a.k.a. “Billy the Brush,” who produced thousands of quality fake paintings; and about Max Brandrett, the protege of Keating and a hugely colourful figure in the world of art forgery. Some of these characters went to jail for their efforts. After serving time, they became celebrities. Some, like Brandrett and Mumford, are now doing quite well financially, selling copies of great art under their own names, rather than passing off fakes. One of the sellers is Jim Hartey of the Global Art Gallery at the Bridge House Antiques Market at Langham, England. Hartey is selling great imitations of Chagall, Picasso, Modigliani, and Stubbs. All are the products of William “Billy the Brush” Mumford.

In an article in Dorset Life magazine about Mumford, titled “Art for Art’s Sake,” Hartey is quoted as saying, “Billy can paint as well as many of the greats, yet none of them could paint like the others. The major art houses were taken in and they hate him for it. Of the 1,100 paintings he made only forty came back.” Mumford’s work did not include my Krieghoff paintings. However, I was getting warmer. Curiously, coincidentally, or serendipitously, the U.K. Daily Express on October 7, 2020, carried an interview with Brandrett. Why was this interview important to me? Simply because all roads seemed to be leading to Brandrett as the skilled hand that had painted the Brighton Krieghoffs. I had sent images of my Krieghoffs to David Henty and to “Billy the Brush.” They, along with Peter and Joanna Bryan, were ninety-nine-per cent convinced that the paintings were the work of Brandrett. Brandrett had been a friend of Gabrio Bonaveri of La Dolce Vito fame and frequented the restaurant to engage in Bonaveri’s art-for-food exchange and to sell him paintings. Somewhere along the line, someone, perhaps Tom Keating, had inspired Brandrett to realize that there was money to be made in the Krieghoff potboiler business.

I tracked Brandrett down and engaged in a series of most spirited email exchanges followed by several phone conversations. I then sent him images of my paintings, and he responded: “Jon, it is my work. Tom [Keating] did not do detailed paintings. Tom did shipping scenes and Dutch winter paintings. Good to see mine again, ‘quite cracking’and very good.” Brandrett told me that he had produced these paintings in some quantity years previous but could not recall exactly how many. One thing is certain: The quantity produced was much greater than the dozen I acquired. Many others are still out there. When I remarked to him that he had done an excellent job with the Krieghoff signature, he replied, “That is the easy part. You just trace it out of a book.”

A documentary is being made about Max. David Henty is doing TV shows. “Billy the Brush” seems to be doing more than okay.

A winter scene painted by art forger Max Brandrett. (Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea / Photography by Doug Nicholson.)

Detail of a perfect reproduction of Cornelius Krieghoff’s signature (from the painting to the left). Brandrett eventually admitted to the author that he had traced the signature from a book. (Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea / Photography by Doug Nicholson.)

SLEIGHTS OF HAND

This rogue’s gallery of immensely skilled art forgers fooled experts everywhere.

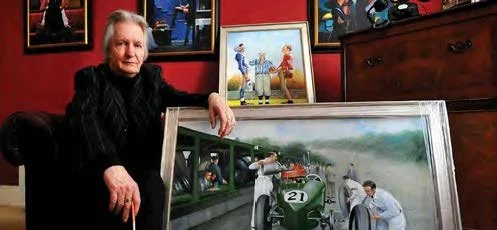

David Henty (born 1958)

David Henty is perhaps the world’s best living copyist. From Brighton, England, Henty was jailed in the mid-nineties for forging passports for people fleeing Hong Kong prior to the handover of the territory to China in 1997. While in prison,Henty took an art class and discovered that he had a talent for mimicking other artists. For years, he sold copies of paintings by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Leonardo da Vinci, and Vincent van Gogh. In 2014, a newspaper probe outed him as an art forger. Ironically, the publicity surrounding the story launched his career as a professional art copyist. On his personal website, Henty claims to have fooled “scientists and art critics alike” thanks to his rigorous attention to detail. However, he refuses to fake the signatures of others.

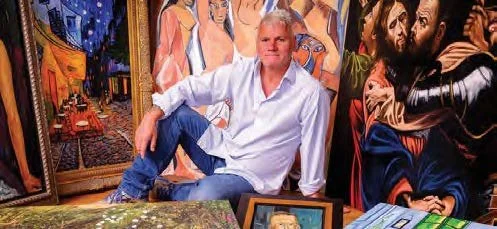

William “Billy the Brush” Mumford (born 1949)

William Mumford of West Sussex, England, sold more than one thousand forgeries, many through the major auction houses of the world. There are likely hundreds in circulation. Some of his paintings sold for as much as thirty thousand pounds (about 51,000 dollars). In 2012, he was jailed for two years for selling a total of more than six million pounds worth of forged paintings to unsuspecting buyers. According to British art dealer James Hartey, “Billy Mumford is one of the greatest living art forgers of all time.” During his career in forgery, Mumford managed to swindle international art experts and sold paintings through Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Bonhams, and other major auction houses. Today, he sells “versions” and interpretations of other artists’ paintings online.

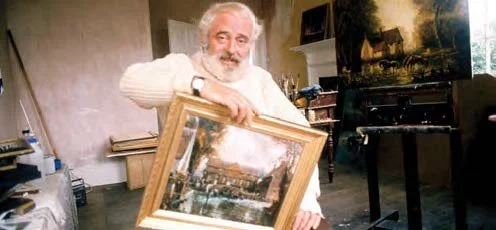

Tom Keating (1917–84)

Tom Keating of Forest Hill, England, began to paint and to sell forged art in the early 1960s. According to media reports, he sold more than two thousand fake paintings, earning several million dollars before his duplicity was discovered in the 1970s. In 1966, Keating met Max Brandrett — the art forger who likely painted the author’s fake Krieghoffs. Keating, who also produced Krieghoff forgeries, became Brandrett’s mentor in the forgery game. In an online article about the world’s greatest art forgers, writer Adriana John called Keating “a singular character among the ingenious forgers. His aim was not merely to make a fortune. It was rather to dismantle the entire system of the art business, which he hated on principle. He believed it to be rotten and corrupt, where credit went to those undeserved.”

Max Brandrett (born 1948)

A skilful painter, Barnardo boy, street hustler, and art forger turned celebrity, Max Brandrett of East Sussex, England, most likely painted the Krieghoff potboilers. According to a November 2020 article in the British newspaper Daily Mail, “Max the Forger” was jailed three times for faking famous masterpieces: “Max left Barnardo’s Children’s Home to join the circus at age fifteen — where he groomed the elephants for two years and painted the trucks, which prompted him to study art.” Brandrett’s chance meeting with art forger Tom Keating in 1966 set him on a course to be the hand that painted the “Brighton Krieghoffs.” Where the remainder of Brandrett’s Krieghoffs are today, no one is quite sure. Brandrett, meanwhile, continues to sell copies of other artists’ works — but under his own name.

Krieghoff fakes are everywhere. Dennis Reid once said to me, “There has long been a rumour of a Krieghoff ‘factory’ somewhere in Europe.” When I repeated the comment to Peter Bryan, he said, “Europe is the Krieghoff factory.” Krieghoff fakes are everywhere. Dennis Reid once said to me, “There has long been a rumour of a Krieghoff ‘factory’ somewhere in Europe.” When I repeated the comment to Peter Bryan, he said, “Europe is the Krieghoff factory.”

A company named Freemanart Consultancy provides a service of “fake and forgery detection.” About Krieghoff, its website states: “Worthy of note, some serious concern, and caution, is that the notorious British faker of paintings, Tom Keating, admitted to having painted hundreds of fake Krieghoff paintings in his illustrious career. None of which have been recovered to this day. With, undoubtedly, many clearly making their way into private collections and Canadian Galleries across the Dominion.”

Cheating the Toll, a Krieghoff copy possibly by art forger Tom Keating. (Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea / Photography by Doug Nicholson.)

Bilking the Toll Gate, an 1861 painting by Cornelius Krieghoff. (McCord Museum, M967.100.14.)

I was still uncertain about the scope and scale of the Brighton Krieghoff production. Subsequent correspondence with Peter Bryan began to paint a picture (pun intended) of the magnitude of the enterprise. Bryan told me that he had purchased a “small collection” from Bonaveri, which he sold on eBay to a trader in New York. Bonaveri, according to Bryan, had sold some at local auction, and, apparently, I purchased the rest.

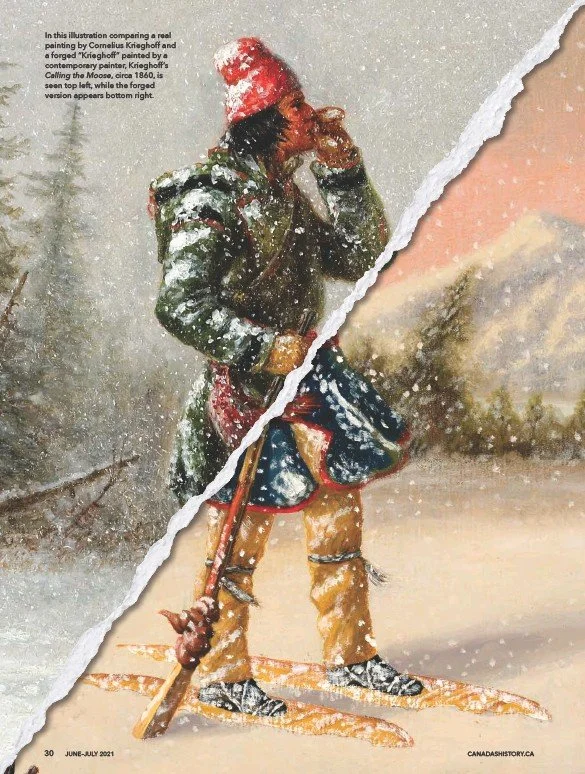

In this illustration comparing a real painting by Cornelius Krieghoff and a forged “Krieghoff” painted by a contemporary painter, Krieghoff’s Calling the Moose, circa 1860, is seen top left, while the forged version appears bottom right. (Top half: The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario, 2009/398; Bottom half: Artwork courtesy of Jon Dellandrea / photography by Doug Nicholson.)

Bryan reminisced, “I remember seeing a parcel of Krieghoffs whilst having dinner with Gabrio, and they were spattered with white emulsion [paint] from careless decorating, leaving the pictures on the wall, I think. Also …Gabrio liked to cook at the table, which was popular, but made a bit of a mess with the smoke, steam, tomato splashed [on the paintings] et cetera. He asked Albert Williams [a well-known floral painter] to clean them.” Joanna Bryan told me that Williams tended to over-clean, which is the likely explanation for why the paintings arrived in such shiny condition.

As for Bonaveri, he died in 2012 at the age of seventythree. A tribute note produced for his funeral stated, “A tutti coloro che conobbero e l’amarono perché rimanga vivo il suo ricordo” (To all those who knew and loved him so that his memory remains alive). The residue of the Wild West is still with us. As one Brighton art figure said to me of the Brighton crowd,“You wouldn’t let any of these guys marry your sister, and they would take credit for the Lindbergh kidnapping if they thought it would bring them greater fame and notoriety.” Tom Keating’s many Krieghoff paintings are unaccounted for. Max Brandrett’s brilliant potboilers are scattered across Europe and North America. Many galleries and private collections contain valued examples of the great work of Cornelius Krieghoff that are actually forgeries.

In 1977, Tom Keating and writers Frank and Geraldine Norman collaborated on a book, The Fake’s Progress: Tom Keating’s Story. The foreword begins: “This is not the story of an international jet-set picture faker. It is the story of a Cockney housepainter with a burning desire to be an artist and an extraordinary facility for innovation.”

On fake Krieghoffs, Maclean’s magazine in 1979 had this to say: “The forgery problem in the works of Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872), one of Canada’s most internationally famous artists, is legendary. Dr. J. Russell Harper, a leading Krieghoff scholar who returned earlier this year from testifying at the Keating trial in London, believes that of the 200 Krieghoffs Keating claims to have done, none has yet found its way into Canada. This is small relief in light of the fact that of the 1,200 Krieghoffs that Harper has examined in Canada, 800 are ‘wrong.’”

Notwithstanding Harper’s observation, Geraldine Norman, in the preface to The Tom Keating Catalogue: Illustrations to The Fake’s Progress, observed, “It is not unreasonable to assume that many of his Krieghoffs have found their way to Canada.” Provenance can be faked, but provenance can also be substantiated. The Art Gallery of Ontario houses the wonderful Thomson collection representing some of the best of Krieghoff’s work. No Keating products and no Brighton Krieghoffs are there, but there are many elsewhere. The problem is that we simply do not know where they are all located or when they will appear on the market.

So, are we left with nothing more than the cold comfort of caveat emptor (buyer beware)? I think not. This country is blessed with highly educated and talented art historians and scholars. We have experienced art dealers and more than a few very reputable and equally experienced auction houses. Like any other important investment decision, homework is a really good idea. As Geraldine Norman observed: “The art market, in fact, is a jungle through which the only reliable guide is your own knowledge.”